What a Sporting Director Actually Does

In today’s game the person who sits between the boardroom and the training pitch is more than a bureaucrat – they are the chief architect of a club’s footballing DNA. A sporting director is tasked with building a coherent long‑term plan that survives managerial changes, market swings, and the inevitable pressure of results. The role typically covers six interlocking domains:

- First‑team oversight for both men’s and women’s squads.

- Player recruitment, scouting, and contract negotiations.

- Academy strategy and youth development pathways.

- Medical, sports‑science, and performance optimisation.

- Loan management, ensuring talents gain experience while protecting club assets.

- Overall cultural and tactical philosophy that ties all departments together.

Unlike a manager who focuses on the next match, the sporting director must juggle immediate squad needs with a 5‑ or 10‑year vision. That means analysing data, nurturing relationships with agents, monitoring market trends, and constantly communicating with owners, CEOs, and coaching staff.

Sevilla legend Monchi (Moisés Henríquez) has often described the position as the "nerve centre" of a club. He argues that without a dedicated professional to harmonise recruitment and development, clubs stumble into ad‑hoc buying sprees that rarely deliver sustainable success.

High‑Profile Cases: From Monchi’s Mastery to Ashworth’s Fallout

Monchi’s résumé reads like a blueprint for modern football success. At Sevilla he turned a modest budget into multiple Europa League titles, largely by spotting undervalued talent—players such as Sergio Ramos and Dani Parejo—then selling them for massive profits. His move to Paris Saint‑Germain and later to a newly formed role at Aston Villa shows that clubs now actively hunt for visionary directors who can replicate that model.

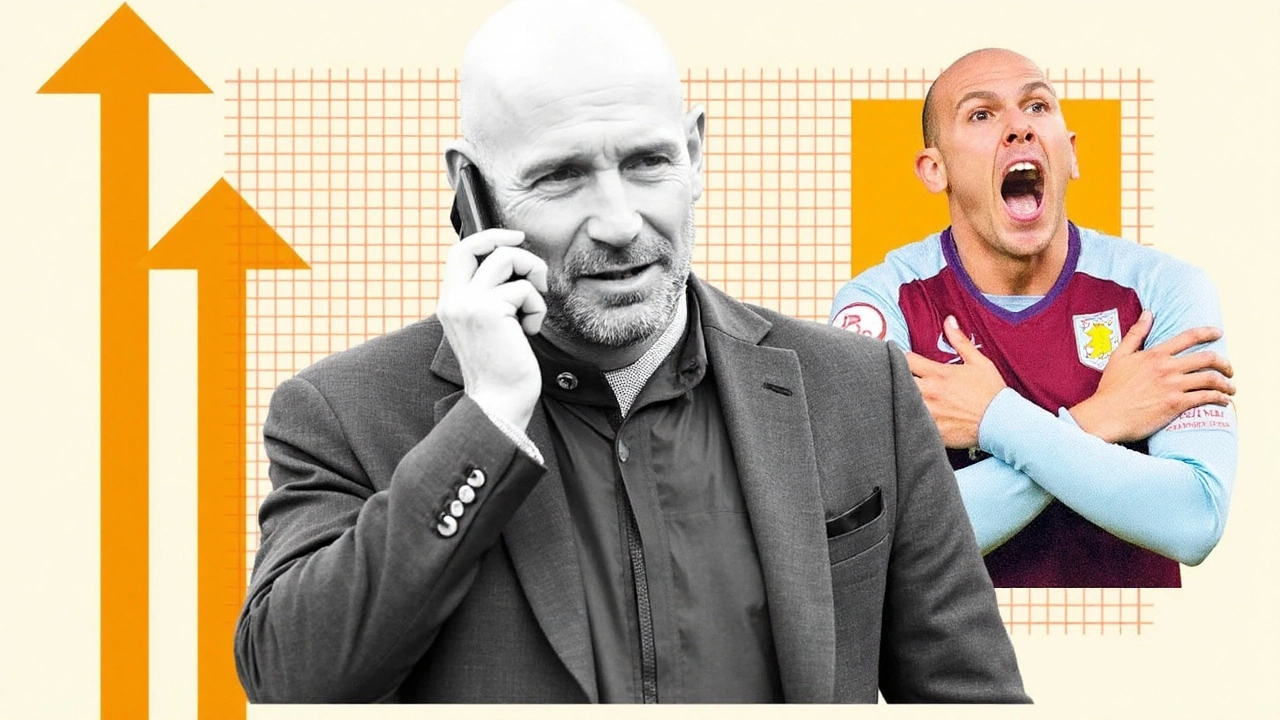

Contrast that with Dan Ashworth’s brief stint at Manchester United. A former FA elite‑development chief who had built reputation at Brighton, West Brom and Newcastle, Ashworth arrived at Old Trafford with a hefty £182 million summer spend on five signings. Within months, only defender Noussair Mazraoui seemed to justify his fee, while the rest of the acquisitions faded into obscurity.

The fallout was swift. After a loss to Nottingham Forest, owners called Ashworth into an urgent meeting and announced a mutual termination. Insider reports suggest that Sir Jim Ratcliffe, United’s lead investor, felt Ashworth lacked the interpersonal swagger needed to navigate the club’s complex hierarchy. The episode underscores a harsh reality: even a seasoned director can be dismissed if his player‑shopping record does not translate into on‑pitch performance.

Yet Ashworth’s story also contains a twist of irony. He had backed Swedish striker Viktor Gyökeres for a modest £1 million move from Brighton to Coventry in 2021. Gyökeres has since exploded, scoring 68 goals in 72 games and attracting offers north of £80 million. United’s new manager, Ruben Amorim, is reportedly eyeing the Swede—a reminder that a director’s vision can sometimes be ahead of his current club’s execution.

Across the Premier League, the majority of top‑flight teams now employ some version of a sporting director. Liverpool’s Michael Edwards, Manchester City’s Txiki Begiristain, and Chelsea’s recently appointed director of football illustrate a growing consensus: strategic continuity behind the scenes is as vital as tactical acumen on the touchline.

Nevertheless, a handful of clubs still operate without a single point person. Chelsea, Newcastle, Sheffield United, West Ham and Wolves distribute the duties among multiple executives, hoping to mimic the benefits of a dedicated director. Critics argue that this fragmented approach can lead to disjointed recruitment and a lack of cohesive club identity.

Looking back, the role of sporting director has morphed from a simple liaison role in the 1990s to a data‑driven, multi‑disciplinary position. Early adopters like Sir Alex Ferguson’s “Director of Football” at Manchester United (before the role fell out of favour) paved the way, but the modern incarnation relies heavily on analytics, scouting networks spanning continents, and sophisticated contract structuring.

Future challenges loom large. Transfer fees continue to inflate, and the pressure to deliver instant results grows louder. Directors will need to balance the temptation of marquee signings with the patience required to cultivate home‑grown talent. Alignment with club ownership will be non‑negotiable; philosophical clashes—as seen between Ashworth and Ratcliffe—risk derailing even the most capable professionals.

Moreover, the rise of women's football adds another layer of responsibility. Many sporting directors now oversee both men's and women's first teams, ensuring resource allocation, scouting, and development pathways are equitable and mutually reinforcing.

In short, the sporting director sits at the heart of a club’s long‑term health. Their success is measured not just in transfer balances, but in the seamless progression of academy graduates to the senior squad, the consistency of playing style across age groups, and the financial sustainability of the transfer market strategy. As football budgets swell and competition intensifies, clubs that neglect this role risk becoming short‑term spenders rather than builders of lasting legacies.

Write a comment